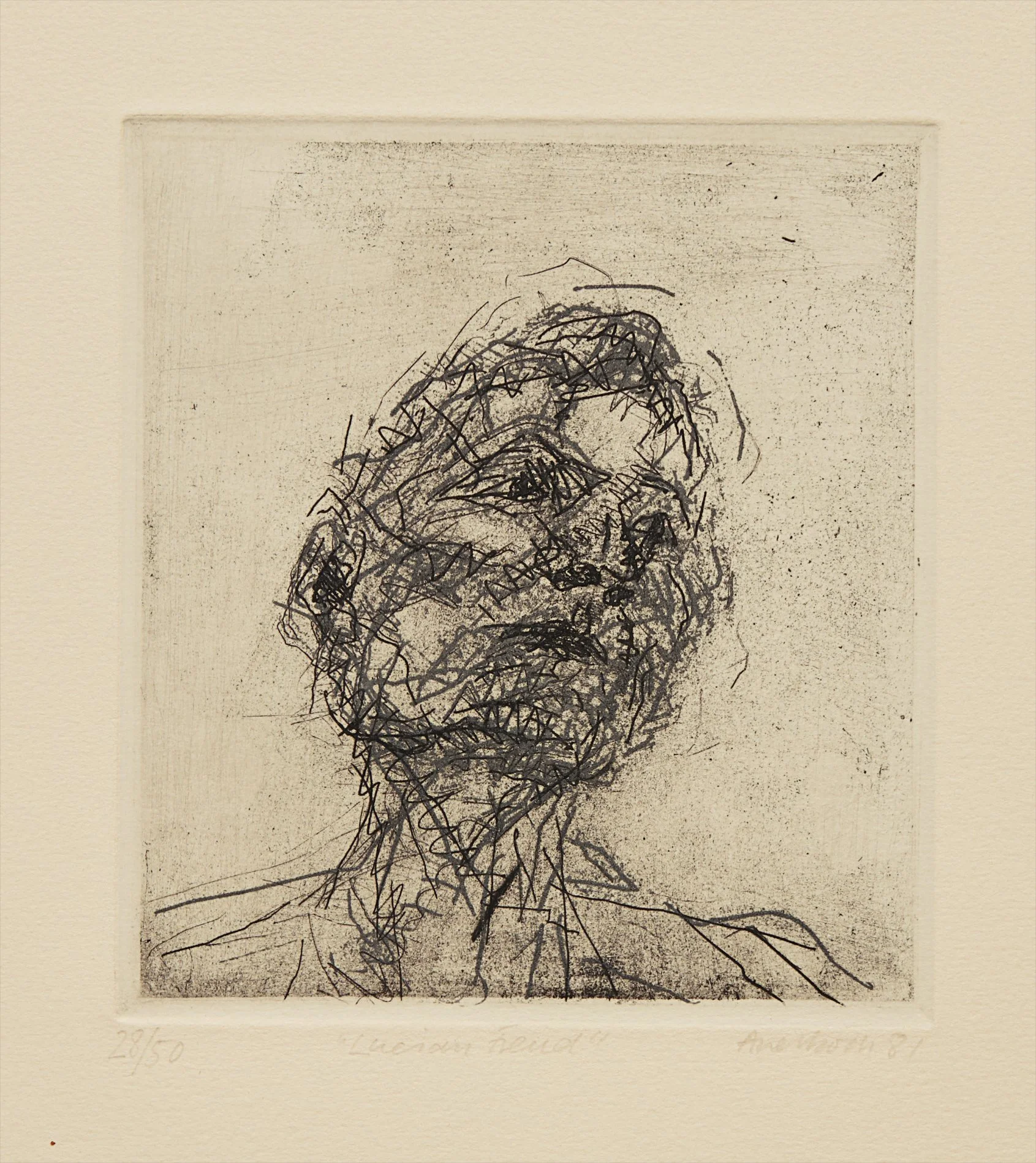

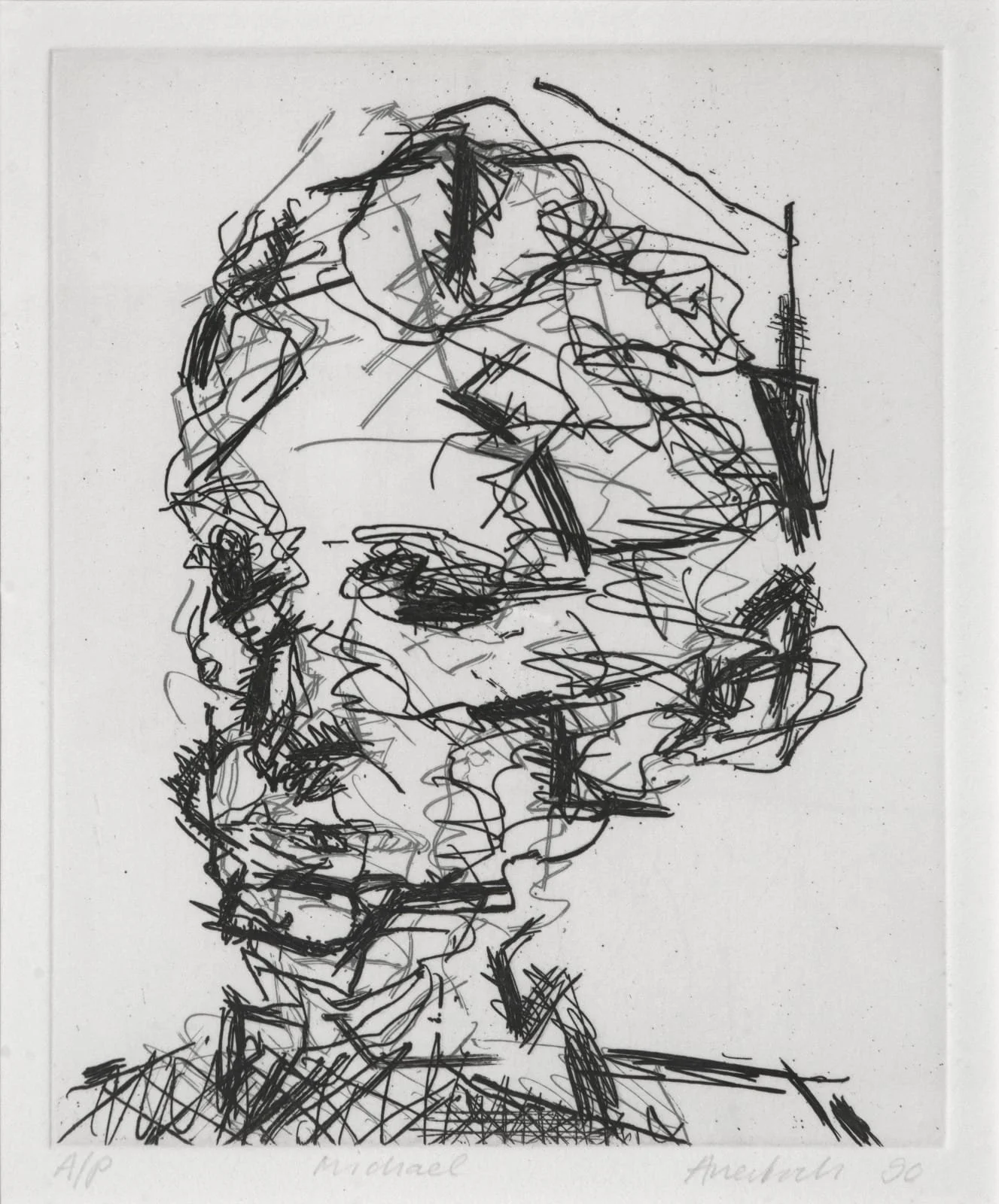

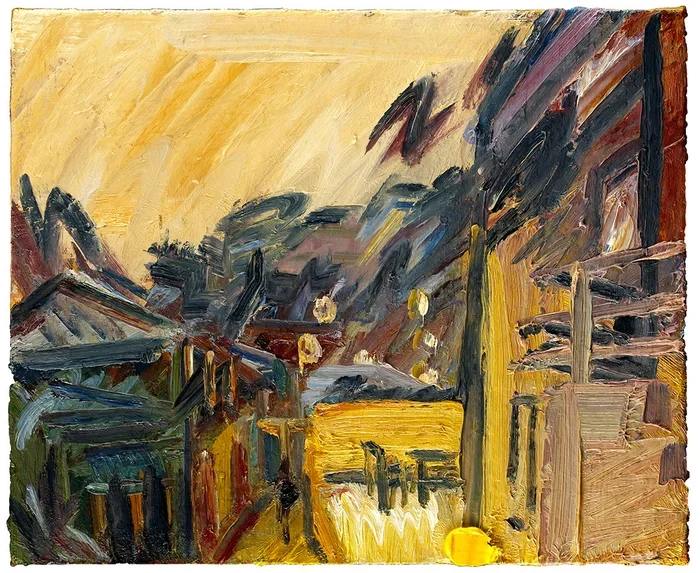

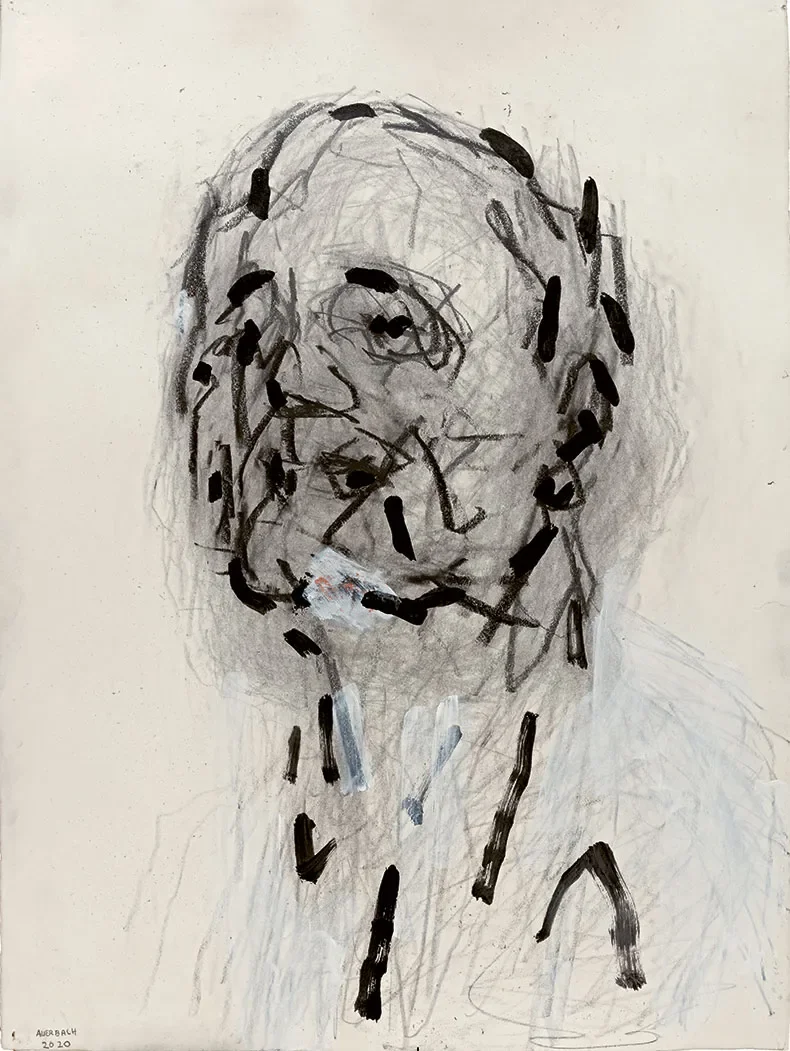

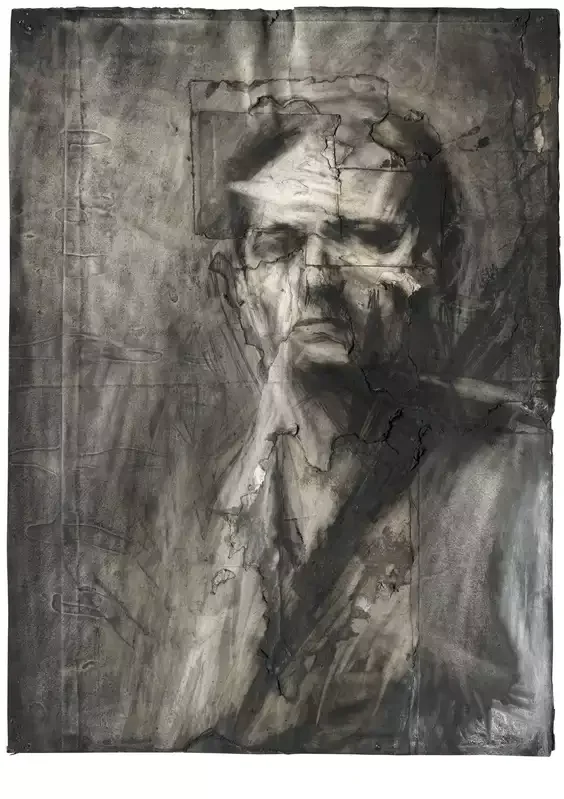

Another British portrait artist…say hello to the work of Frank Auerbach.

Auerbach was born in Berlin to Jewish parents and he escaped Nazi Germany for England in 1939. His parents, who stayed behind, unfortunately died in concentration camps. He had a very traditional English education and only got into art late in boarding school. He came close to pursing acting, but in the end, he attended the Royal College of Art and had his first solo show in 1956. He also taught art throughout his career.

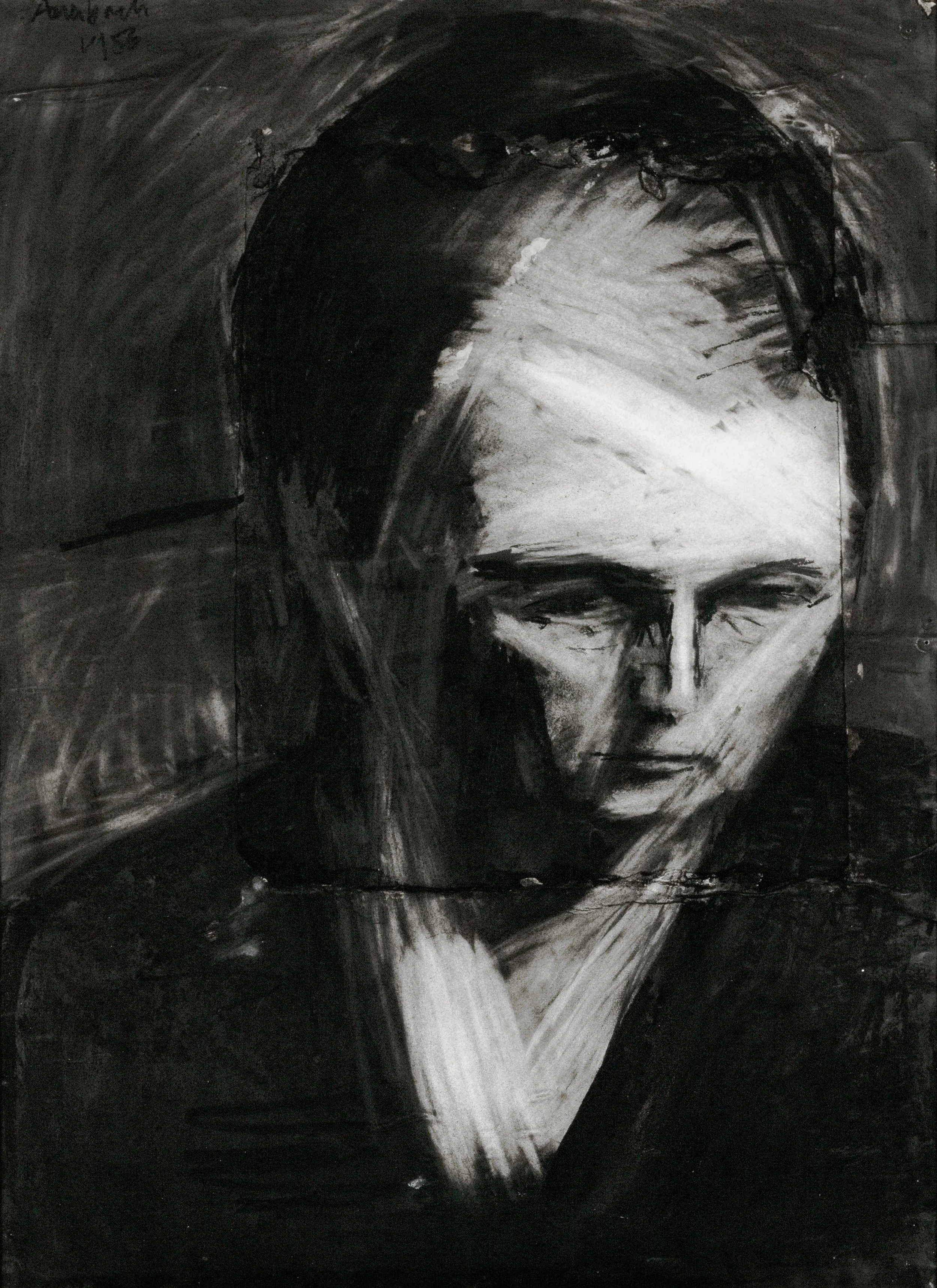

His work stunned critics at the time, reading more like sculpture than painting or drawing. A critic at the time wrote, “in spite of the heaped up paint, these are painterly images, not sculptures ones…they make their point because of their physical structure…they have the psychological impact of a painting and the weight of a sculpture.”

What has intreguied and beguiled me about his work since I first was introduced to it is how heavily drawing plays a role. I think it’s that strong tie to draftsmanship that gives these pieces that “sculptural” feel that his critics often site. And even more than that, there is an emotional heaviness here, a sense that he wasn’t just drawing or painting his subjects likeness, but also trying to get at something deeply personal about them, as individuals.